As an Arab, it’s a complete toss up whether you end up spawning as a Levantine Arab in war-torn Palestine, or a Gulf Arab living a life in London so lavish that it’s unfathomable to the average person, or if you spawn as a North African, risking your life to cross the Mediterranean for a better future. The disparities between Arabs are striking. The fragmentation that exists within the Arab world makes unity seem like a utopian dream, but this disintegration can be partially explained through history.

Political divide of the Muslim community can be traced back to the first Fitna, the first Civil War, when the Prophet’s cousin ʿAlī and the governor of Syria, Muʿāwiya, contested the caliphal succession. However, it wasn’t until the Abbasid period that the Arab community experienced serious political fragmentation. Whilst the fleeing Umayyads established their own dynasty in Spain, local dynasties emerged in North Africa and Iran during the Abbasid era. Topography played a key role in this; mountainous regions were often more prone to uprising and rebellion, whilst plains were easier to assimilate into an empire. The extremities of the empire – the Maghreb, for example – were harder to integrate into central governance. The Ottomans faced a similar problem; the French rapidly penetrated Ottoman Algiers, far from the Sultan’s centre of Istanbul.

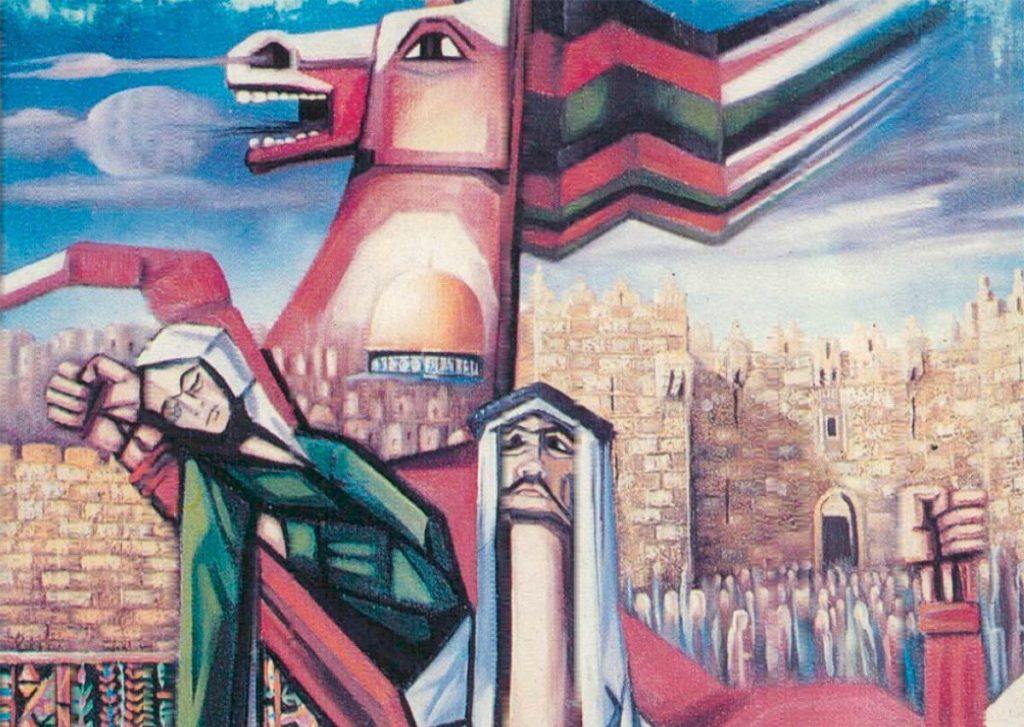

As the Ottoman Empire weakened, the need to express Arab identity, as opposed to pan-Islamic identity, intensified. Egypt found itself turning to its Pharaonic past to emphasise individuality, whilst Lebanon turned to its Phoenician origins. In North Africa, the occupying French played on the Berber-Arab divide, convincing the Kabyles in Algeria that they were more secular, more refined, and inherently more democratic than the Arabs. Colonialism played a huge factor in the fragmentation of the Arab world. Whilst many Arab countries were exploited for their natural resources, the British assumed that the Saudis didn’t possess any oil and, consequently, they were never colonised. Many Arab leaders collaborated with their colonial masters in order to ensure that they will rule part of their land post-independence, most notably, the Sharif of Mecca and King Abdullah of Jordan. Most famously, T.E. “Lawrence of Arabia” encouraged Arab tribes to revolt against the Ottomans. It is no surprise that this need to express Arab identity resulted in the nahda, the revival of Arab culture, language and literature after Ottoman supremacy.

Post-independence, there were efforts on the part of Arab leaders to create some form of unity, but this was rather short lived. Only a decade or even less post-independence, ideological differences emerged between Arab countries; socialists versus capitalists, monarchies versus Republics, to name a few. And of course, the Cold War only exacerbated these already existing divides. The Arab world became polarised during the Cold War as the US and the USSR rushed to secure alliances with countries that fit their ideologies and their ambitions in the region. It is worth mentioning that the Palestinian cause may have brought about Arab unity, but even prior to the 1948 nakhba, Arab leaders were divided, completely fragmented and totally disorganised. We know from the memoirs of Fawzi al-Qawuqji, one of the most prominent advocates for the Palestinian cause, that he was questioned by Arab leaders as to why he kept ‘provoking’ the settlers. We know from his memoirs that he was dealing with Arab leaders of new states, states that only just gained independence. Ultimately, they were fragmented then just as much as they’re fragmented today. Even Gamal Abdel Nasser, the godfather of the pan-Arab movement, always reiterated that he saw Egypt as the nucleus of the movement, expressing a nationalist Egyptian sentiment as opposed to a pan-Arab sentiment in his speeches.

Few cities expose these divisions as vividly as London. A cosmopolitan hub, London is home to Arabs from across the MENA. Whilst North Africans and Levantines are more often engaged in regular employment with modest wages, Gulf Arabs are associated with extravagant displays of wealth, purchasing entire blocks of apartments (during a housing crisis) and indulging in chocolate-covered strawberries at Harrod’s.

So, is Arab unity an unattainable ideal? Will it ever be realised within our lifetimes? While perhaps optimistic, it is not entirely impossible. Each Arab state possesses its own history and identity. Yet, as disparities gradually diminish and as nations recover from the traumas of colonialism, civil wars, and the Arab Spring, a new form of cooperation may emerge. This unity may not manifest as a single state, but rather as pragmatic alliances built upon mutual interests and shared needs. It is, at the very least, conceivable.

References

Badawi, M.M. (1992) Modern Arabic Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parsons, L. (2016) The Commander: Fawzi al-Qawuqji and the Fight for Arab Independence 1914–1948. New York: Hill and Wang.

Rogan, E. (2009) The Arabs: A History. London: Penguin Books.

Leave a comment