“يا للغرابة. يا للسخرية. الإنسان لمجرد أنه خلق عند خط الاستواء، بعض المجانين يعتبرونه عبدا وبعضهم يعتبرونه إلها.”

“How strange! How ironic! Just because a man has been created on the Equator some mad people regard him as a slave, others as a god. Where lies the mean? Where the middle way?”

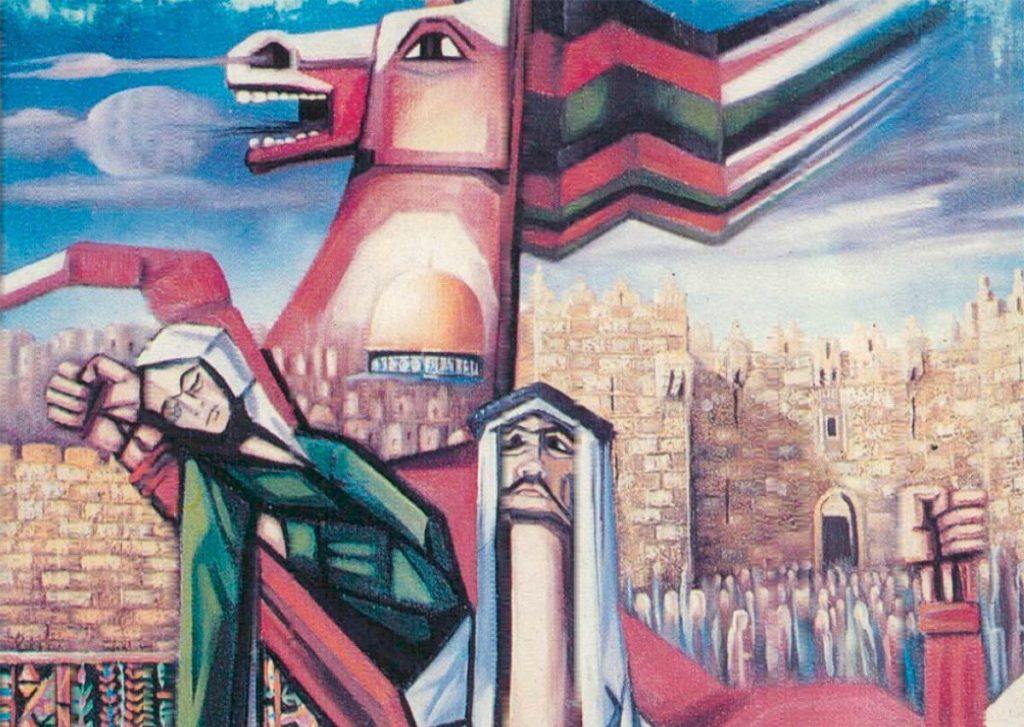

This is the question the unnamed Narrator of al-Ṭayyib Ṣāliḥ’s controversial novel asks himself after hearing of Muṣṭafā Saʿīd’s strange tales seducing European women by presenting himself as an “exotic Arab African”. His story only becomes more bizarre when it is revealed that each one of these women has ended up dead.

Season of Migration to the North begins when the Narrator returns from his studies in England to his Nile-side village in Sudan, Wad Ḥāmid, after an absence of seven years in England. He finally feels at home in the countryside and amongst his people but his return to tranquillity is interrupted when he hears the foreign tones of an English poem being recited by Muṣṭafā, a character shrouded in mystery yet revered by the entire village. Because of the Narrator’s similar experience as a traveller in Europe, Muṣṭafā decides to tell him his story and, chapter by chapter, his dark past is unspooled before the reader.

Muṣṭafā’s tale is loaded with antitheses: the coloniser and the colonised, man and woman, foreign and native, modernity and tradition, slaves and gods. All these contrasting elements create a crippling sense of duality in Muṣṭafā, rendering him the frightening product of decades of colonial oppression. Tayeb Ṣāliḥ reminds us that the effects of colonial horror do not end when a country wins independence, and without addressing the colonial dynamics that remain within the minds of the colonised, they are left drowning in a sea of confusion and hate.

Intelligence As a Weapon

‘Soon I discovered in my brain a wonderful ability to learn by heart, to grasp, to comprehend. On reading a book it would lodge itself solidly in my brain. No sooner had I set my mind to a problem in arithmetic than its intricacies opened up to me, melted away in my hands as though they were a piece of salt I had placed in water.’

One of Muṣṭafā’s most notable characteristics is his intelligence. He surprises the Narrator by having a superb command of English, his grandfather calls him a “most excellent person”, and the rest of the village people also view him as highly intelligent and educated. In fact, what makes Muṣṭafā initially interested in the Narrator, is his completion of a doctorate in England. Interestingly, all these qualities have an underlying implication of colonial superiority because what makes Muṣṭafā and the Narrator respected and admired is not merely the fact that they are educated but educated by the “correct” institutions and their proximity to Britain.

Muṣṭafā has also always been aware of his own intelligence. He describes his mind as a ‘sharp knife’ that exceeds all expectations by ‘biting and cutting like the teeth of a plough’. During his school years in Sudan his teachers are astonished by his brilliance, but his classmates regard him with either admiration or envy. An Englishman tells him that ‘This country hasn’t got the scope for that brain of yours, so take yourself off’. The admiration from authority figures, and the envy Muṣṭafā feels from his peers, distances him from his fellow countrymen. The distance is made greater by his lack of positive parental figures; he never knew his father and his mother is described as cold and uninterested in his life. This ego combined with the violent imagery Muṣṭafā uses to describe his intelligence reveals his dangerous superiority complex and how he envisions his mind as a weapon.

Ṣāliḥ highlights that infrastructures established by the British in Sudan, often portrayed as beneficial development projects, were instead used to advance the colonisation of Sudan. This was done by physically infiltrating the country by building railways to transport soldiers, but also psychologically through the schools which were built ‘to teach (the Sudanese) how to say “Yes” in their (the British) language’. Here, Muṣṭafā implies that the British schools in Sudan brainwashed their students into accepting British superiority while distancing them from their own culture. These are the first cracks in Muṣṭafā’s sense of identity, and throughout the novel, they only grow larger.

The Two Rooms

‘How ridiculous! A fireplace — imagine it! A real English fireplace with

all the bits and pieces, above it a brass cowl and in front of it a quadrangular area

tiled in green marble, with the mantelpiece of blue marble; on either side of the

fireplace were two Victorian chairs covered in a figured silk material, while

between them stood a round table with books and notebooks on it.’

Ṣāliḥ represents the fragmentation of Muṣṭafā’s identity through two rooms: one in London and one in Sudan. After Muṣṭafā’s death, the Narrator enters his basement which demonstrates Muṣṭafā’s obsession with the English. It is decorated like a Victorian sitting room with a perfect replica of an English fireplace, which in the blistering heat of a Sudanese village is entirely useless. The room is filled with books on countless subjects, but the Narrator notices that not a single Arabic book is housed in its many shelves. Muṣṭafā’s basement in Sudan is in direct contrast to his room in London which he calls his ‘den of lethal lies’. This room, in which he brings all his European lovers, is perfumed with ‘sandalwood incense’, decorated with ‘ostrich feathers and ivory and ebony figures’ and on the walls hang ‘drawings of forests of palm trees along the shores of the Nile’. Muṣṭafā recognises that the women he meets in England are attracted to this exotic, fetishised version of his identity and uses these distortions to manipulate his lovers.

‘When she saw me, she saw a dark twilight like a false dawn. Unlike me, she yearned for tropical climes, cruel suns, purple horizons. In her eyes I was a symbol of all her hankerings.’

When Muṣṭafā is wooing Isabella Seymour he talks about his village by the Nile with magical romanticism, ‘when I’m lying on my bed at night, I put my hand out of the window and idly play with the Nile waters till sleep overtakes me’. The game Muṣṭafā plays leads him to look at his own country not as a home but a romantic dream that he tells his lovers.

But this perverse roleplaying is a two-way street because just like his lovers, he also fetishises what is new and foreign; he sees himself as ‘the South that yearns for the North and the ice’. This obsession seems to have stemmed from his relationship with a British woman, Mrs Robinson, when she hired him as a guide in Egypt. Muṣṭafā is fascinated by her pale skin, her smell and the way in which she was ‘tender to (him) as a mother to her own son’. His relationship to Mrs Robison could be described as Freudian as he deeply cherishes her maternal affection but at the same time is sexually aroused by the touch of a foreign woman. His chase after this attraction for Mrs Robinson is evident when Muṣṭafā meets Isabella and he smells ‘the odour of her body, that odour with which Mrs Robinson had met me on the platform of Cairo’s railway station’. The first foreign woman Muṣṭafā meets has a clear impact on him and is perhaps the trigger that awakens his obsession and his conflicting relationship with them as simultaneous lovers and enemies.

His entire life, Muṣṭafā has had to battle with contrasting elements: the uncaring mother and the overly affectionate one, his sexual attraction mixed with his desire for motherly attention, his jealous Sudanese classmates and the British teachers who praise him, his fetishisation of Sudan and his fetishisation of Britain. The final chapters in Muṣṭafā’s basement are a culmination of his attraction to what he calls, the North. The basement also represents his feeling of isolation within his own home country and how he feels like he must hide away his “foreignness” which sticks out like a fireplace in the desert.

Constructing Othello

‘Yes, my dear sirs, I came as an invader into your very homes: a drop of the poison which you have injected into the veins of history ‘I am no Othello. Othello was a lie.’

As Muṣṭafā learns more about the colonial power dynamics at play between Britain and Sudan his confused attraction for Britain as a foreign and exotic country is blended with deeply harboured hatred for its colonial history. Although Muṣṭafā embraces and plays the stereotype of the “exotic African”, his intent is not just to seduce women but to reverse the roles of oppression. He calls himself an ‘invader’ a ‘coloniser’ and even says that he will ‘liberate Africa with his penis’. In his basement, it is revealed that this dynamic even reached Muṣṭafā’s bedroom since the Narrator lovers revere him as a God or a slave master. The Narrator finds notes from Isabella Seymour calling Muṣṭafā, ‘O pagan god of mine’ and a picture of Ann Hammond dressed in an Arab robe with a note written in shaky Arabic, ‘your slave girl’. The most shocking revelation from the basement chapters is Muṣṭafā’s account of Jean Morris’s murder. The metaphor of Muṣṭafā’s sharp intellect represented as a dagger makes a literal reappearance because he stabs Jean in the chest during intercourse, something he describes as her final wish.

During his trial Muṣṭafā is accused of being ‘an Othello’. He strongly denies this despite the similarities of his story with that of Shakespeare’s play in which a ‘Moor’ (a European exonym for a Black Muslim) is tricked into murdering his wife, convinced by his trickster advisor, Iago, that she has been unfaithful. In the play, Othello does his best to integrate into European culture and, despite facing discrimination he is mostly accepted and holds a respected position in the army. However, due to his naivety and trust in Iago, he is manipulated into fulfilling the role of the “savage African”. The irony in both Shakespeare’s play and Ṣāliḥ’s novel is that it is precisely because of their efforts to escape the narrative which is perpetuated by colonial powers that they are bound to their fate. Othello tries to subvert the narrative by appealing unwisely to his European peers and Muṣṭafā tries to subvert the narrative by attempting to oppress the oppressor, but by constructing a fictional identity, they are both destined to fall on their swords.

Let us also remember that many of the deaths in the novel are women. What Muṣṭafā fails to recognise in his attempt to avenge Africa is that he ingests the same hatred, the same poison that the colonisers ‘have injected into the veins of history’. In the background of Muṣṭafā’s story is the sexual violence to which the Sudanese women of his village are subjected. Wad Rayyes, for example, is a known predator in the village who often talks about his adventures kidnapping young slave girls and stripping off their clothing. After Muṣṭafā dies, Wad Rayyes forces his widow, Ḥosna bint Maḥmūd, to marry him. Despite her pleas to remain single under the protection of the Narrator, her father marries her off. When the village people start hearing Ḥosna’s screams from Wad Rayyes’s bedroom, they do nothing, believing that Wad Rayyes has finally achieved what he wanted. However, it is only when they hear a man’s screams that they storm into the house to see Wad Rayyes murdered and Ḥosna dead after committing suicide.

The narrative of oppression is built on the notion of superiority and inferiority. Whether it shows itself through the racism in Europe or the misogyny in Sudan, it is the same hateful tale that seems to control all its characters. It is unclear why Jean wanted Muṣṭafā to kill her, however if she was so enthralled by his narrative, perhaps she strangely yearned for the tragic ending of the story of Othello and his wife.

The Lie and the Germ of the Disease

‘They imported to us the germ of the greatest European violence, as seen on the Somme and at Verdun, the like of which the world has never previously known, the germ of a deadly disease that struck them more than a thousand years ago.’

The terms ‘lie’, ‘germ’ and ‘disease’ appear throughout the novel, and it is difficult to pinpoint what Ṣāliḥ might mean by these words. We can nevertheless infer a relation between these words and ideas of false identity, colonialism, racism, violence and hatred.

Muṣṭafā is consistently referred to as ‘the lie’ by the Narrator and by himself. Muṣṭafā calls his life a lie, he calls his room in London a ‘den of lies’ and although he denies being Othello because ‘Othello is a lie’ in court he desperately thinks, ‘This Muṣṭafā Saʿīd does not exist. He’s an illusion, a lie. I ask of you to rule that the lie be killed’. Muṣṭafā’s fantastical rooms, his list of dead women, his European literature and his English fireplace are all fabricated elements of an identity that does not exist and that is built on preconceived racist notions of what is a European and what is an African. Muṣṭafā has been infected by what Ṣāliḥ describes as ‘the germ of the disease’ that has existed throughout history.

That said, what exactly is this disease? Muṣṭafā says that he is surrounded by it. When Isabella Seymour enters his bed, he says that she has been ‘infected with a deadly disease’ that will bring her death. Even after he returns to Sudan, he calls his bedroom ‘a spring-well of sorrow, the germ of a fatal disease’ a disease which had ‘stricken these women a thousand years ago’ and it is also ‘the greatest European violence’. Muṣṭafā entrusts his wife and sons to the Narrator in his will before his death because he fears transmitting ‘the germ of this infection to them’. It is strongly implied that Muṣṭafā has committed suicide by drowning himself in the Nile to reduce his influence on his children or perhaps to escape his tortured life. Another possible meaning to the ‘disease’ and the ‘lie’ is the distortion of one’s identity as well as the propagation of distortion. In his childhood, Muṣṭafā became extremely knowledgeable about history and literature without a grounded support from his mostly absent biological parents. His experience with his schoolmates is only of competition and jealousy as he seeks approval from his British teachers. Part of the thousand-year disease is thus a strategy of divide and conquer, separating the Sudanese from Sudan, making him feel foreign in his own country. He then does not see foreign women as individuals but as objects with which he takes revenge on history, and his every action is weighed down by the burden of colonial dynamics. For example, when he takes Isabella Seymour to bed, he imagines the Arab soldiers as they enter Spain and likens her to ‘a fertile Andalusia’.

The disease, germ and lie are all distortions of reality through preconstructed fantasies. The Narrator hints at this when he reads an unfinished poem written by Muṣṭafā:

“The sighs of the unhappy in the breast do groan

The vicissitudes of Time by silent tears are shown

And love and buried hate the winds away have blown.

Deep silence has embraced the vestiges of prayer

Of moans and supplications and cries of woeful care,

And dust and smoke the travellers path ensnare.

Some, souls content, others in dismay.

Brows submissive, others …”

The Narrator is very critical of it and calls it ‘a very poor poem that relies on antithesis and comparisons; it has no true feeling, no genuine emotion.’ His criticism may easily be levelled to Muṣṭafā’s interactions with the world through antithesis and comparisons (white and black, British and African). If this is how Muṣṭafā sees his lovers and if this is how his lovers see him, through a gauze of stereotypes and storytelling, can there really have been any genuine emotion?

The Narrator’s Final Decision

‘Was it likely that what had happened to Muṣṭafā Sa’eed could have happened to me? He had said that he was a lie, so was I also a lie? I am from here — is not this reality enough? I too had lived with them. But I had lived with them superficially neither loving nor hating them. I used to treasure within me the image of this little village, seeing it wherever I went with the eye of my imagination.’

There is an undeniable similarity between Muṣṭafā and the Narrator. Both men have returned to their home country after living abroad in the North and while not much is known of the Narrator’s experience in Europe, after hearing Muṣṭafā’s story he too is terrified of becoming infected with Muṣṭafā’s disease and destroying himself just as Muṣṭafā has done.

What is clear by the end of the novel is that the Narrator has undergone transformation. The first chapters are filled with beautiful descriptions of the village’s rural landscape, ‘the cooing of the turtle-dove’ and the green branches of ‘the palm tree standing in the courtyard of our house’ that makes him feel at home ‘not like a storm-swept feather but like that palm tree, a being with a background, with roots, with a purpose.’ His return to his village comes with a series of childhood memories and he again says ‘No, I am not a stone thrown into the water, but a seed sown in a field’. He seems completely reassured by his feeling of stability in the village. However, after Muṣṭafā’s story, the Narrator experiences an existential crisis as he questions how his imagination and fantasy has coloured his memory of his precious village. Is he, like Muṣṭafā, ‘a lie’ and is he also guilty of romanticising his country as a foreigner does? His repeated reassurances of not being a ‘stone thrown into the water’ or ‘a storm-swept feather’ therefore seem like attempts to try to piece together a shattered identity.

It is important to recognise that Muṣṭafā’s story is not told in chronological order. In fact, the Narrator is told everything by the third chapter of the book while the full extent of Muṣṭafā’s depravity is only revealed to the readers in the penultimate ninth chapter. This is because Muṣṭafā is not necessarily the centre of this novel, rather it is the Narrator’s emotional journey and understanding of Muṣṭafā’s story that dictates the novel’s events. In chapter three, although the Narrator knows everything, it is only after he hears about Wad Rayyes’s abuse against women, the corruption of Sudanese politicians, and the violence in his village that he is truly changed. The beginning of the ninth chapter starts with these lines:

‘The world has turned suddenly upside down. Love? Love does not do this. This is hatred. I feel hatred and seek revenge; my adversary is within, and I needs must confront him’

The Narrator’s vision of his idyllic rural village has been turned on its head and he decides to destroy the den of hatred and disease: Muṣṭafā’s secret room. In a confused moment, the Narrator strikes a match and suddenly sees Muṣṭafā’s face in the darkness however of course it is not the dead man, rather ‘it’s a picture of me (the Narrator) frowning at my face from a mirror’. In this almost supernatural moment, the Narrator sees Muṣṭafā in himself, and this sets him on a rampage looking through all the European books, photos of lovers, letters and the unfinished poem. He ultimately does not destroy the basement. In the Narrator’s words, ‘Another fire would not have done any good. I left him talking and went out. I did not let him complete the story’.

Just as Muṣṭafā attempts to take revenge on his enemy and unwittingly becomes his own enemy, the Narrator too starts to follow in Muṣṭafā’s footsteps of death and destruction. He enters the Nile, swimming just as Muṣṭafā had done, towards his own death. However, just as the Narrator begins to seep into unconsciousness he experiences ‘a violent desire for a cigarette’; an ironic desire to keep living. He begins to struggle and call for help, not letting his story end like that of Muṣṭafā’s because otherwise he would have died as he was born ‘without any volition’ of his own. The Narrator suddenly realises that he has never truly decided for himself during his life and now is the pivotal moment. The moral behind the Narrator’s final decision lies in a refusal to live by the narratives other people tell. Whether it be exotic fantasises of African men, or glorious stories of battle Arab soldiers in Andalusia, or romantic visions of rural villages or depictions of women as prizes to be won and conquered, these narratives are all weaponised to spread violence and hatred. The ‘lie’ and the ‘germ of the disease’ in Season of Migration to the North are distortions of identity as well as reality. At the heart of Ṣāliḥ’s writing is a call to reality. A call to think and to study critically. A call to recognise how both foreign and local powers can shape one’s identity to follow a pre-written path that benefits nobody but the perpetuation of a false narrative. The Narrator’s final realisation is that choosing to live means actively escaping the confines of this lie, not subverting it like Muṣṭafā or working within it like Othello, but by leaving it behind.

Bibliography

Ṣāliḥ, al-Ṭayyib. Season of Migration to the North. Translated by Denys Johnson-Davies. New York: New York Review Books, 2009.

Ṣāliḥ, al-Ṭayyib. Mawsim al-hijrah ilá al-shamāl. 14th ed. Beirut: Dār al-ʻAwdah, 1987..

Leave a comment