Can a writer give voice to the silenced without speaking over them? This question lies at the heart of the controversy surrounding Kamel Daoud’s Houris (2024), a brutal yet beautiful novel that has won France’s prestigious Goncourt Prize while triggering legal action and ethical outrage in Algeria. The book gives a harrowing account of the Algerian Civil War in the 1990s, portraying a mute female survivor whose throat was mutilated and whose family was massacred by Islamic militants. It has provoked accusations from two fronts: firstly, he has “instrumentalised the wounds of the civil war”, particularly one still raw and unreconciled, for a place in the Goncourt hall of fame and secondly, he has exploited personal trauma without consent.

Daoud, now living in exile in Paris, faces criminal charges from the Algerian government for illegally speaking about this civil war. Most importantly, he has been accused of invading the privacy of a woman, Saada Arbane, whose story is remarkably similar to that of the main character, and who was a patient of his wife, a psychiatrist. Arbane claims to have refused his request to use her story on three separate occasions, while Daoud continues to maintain that his book is purely fictional, albeit inspired by the events of the civil war and his own traumatic experience. In the West, Houris is widely celebrated for its emotional depth and density. Yet, in Algeria he is a divisive figure, seen by many to be inappropriately violating personal privacy, exploiting national trauma, and politicising memory, transforming it into fiction whilst it remains an unspeakable truth.

Given that it is forbidden to speak about this specific war, the Algerian government seems to be clearly more concerned with the political implications of Daoud writing this book and exposing the unresolved trauma of the war, than justice for Arbane. With the fame and recognition received from this prize, sales will skyrocket and Daoud will inevitably become a household name across France and wider Europe. In an effort to disseminate even more widespread anti-Arab and anti-Algerian discourse in France, taking him to court disowns Daoud as an Algerian, and wages a diplomatic war against the French.

There is also an unavoidable irony behind this murky lawsuit, no doubt muddied by the Algerian government’s determination to erase the painful living memories of “The Black Decade”. In using his novel to speak up about the (literally) unspeakable atrocities, violence and damage of human rights committed during the Algerian Civil War and in using her as a model on which to expose them, Daoud is simultaneously violating her privacy, her autonomy, and her human rights. He claims that Houris, which follows the woman’s internal monologue to her unborn child, is a feminist work, a “novel about women, for women”. Yet, by using her story without permission, is he not perpetuating the misogynistic culture of silencing and objectification that he publicly condemns? This contradiction raises a difficult question: is it ever possible for a male writer to truly give voice to the silenced without speaking over them?

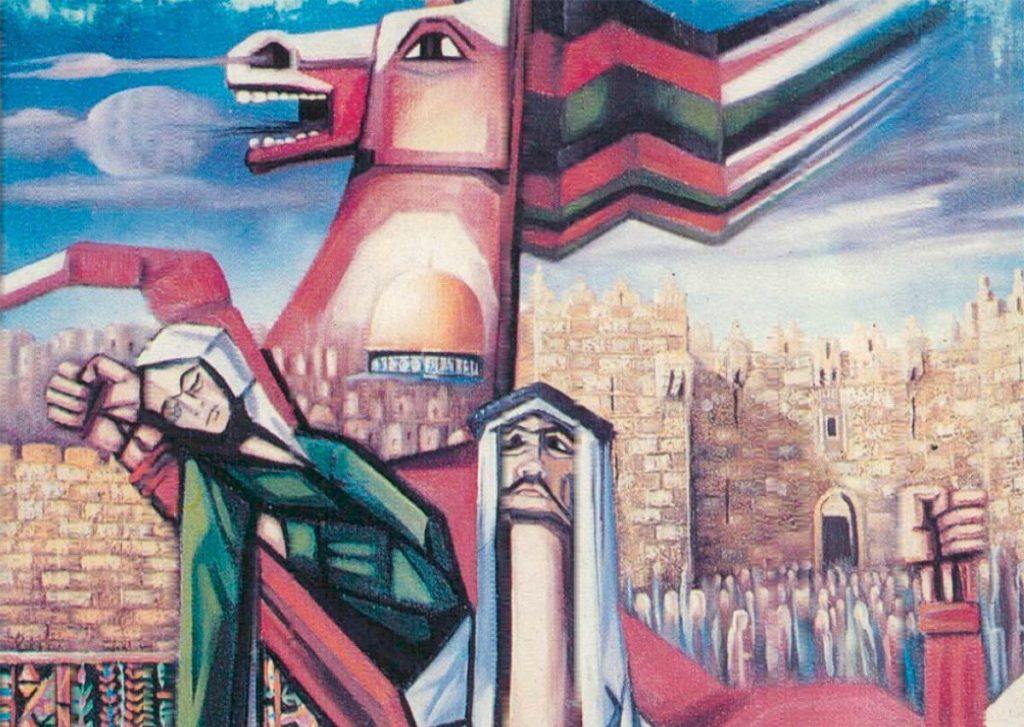

Male-authored trauma narratives, especially in colonial or post-colonial contexts, often risk re-objectifying the very women they intend to empower. The recurring paradox lies in the male author assuming the role of the saviour, transferring the woman’s autonomy from the coloniser to the so-called liberator, thus continuing to deny her of choice and her freedom. This is a role that has been embodied since the beginning of France’s colonial power in Algeria, with Eugène Delacroix’s famous 1833 painting, Women of Algiers in Their Apartment, which captures the Orientalist fantasy of the forbidden gaze on the unveiled, passive women. This colonial gaze on the exoticised ‘other’ persists, even in post-colonial literature. Daoud seems to have fallen unknowingly into the same trap of speaking for, or about the woman, rather than allowing her to speak for herself, attempting to liberate her but only managing to pass her as an object from one male gaze to another. The fact that the narrative is mediated by a male author risks it remaining trapped as a projection, a product of what is only his imagination of her pain. He is speaking through her in an act of ventriloquism rather than liberation.

Daoud is one of the few with the ability and platform to speak at all. Not to do so would be a missed opportunity to honour the memories of the civil war’s victims. In Houris, Daoud literally gives a voice to a woman who is physically unable to speak, and whose child, unwanted and unchosen, serves as a living, breathing reminder of wartime violence. The women of Algeria bore the brunt of the civil war’s horrors, by being raped and violated, and were expected to hide their trauma. The visible evidence of their suffering in the pregnancies that followed made them doubly punished: as victims and as reminders of what society desperately wished to forget.

Daoud argues that it is only normal that people may recognise themselves in a story like this one, which reopens the unhealed wounds of a nation still awaiting reconciliation, still haunted by unhealed violence. The trauma of the war remains vivid, and the blood of the memories remains wet. He claims it is not his intention for his literary work to be politicised, rejecting the role of Algeria’s representative to the Western world that has been imposed on him. But a novel this harrowing, this explicit in its portrayal of systemic violence, is political by nature.

It is through speaking of pain that conflict is resolved. It is through describing the memories of violence, however painful it may be, that violence can be confronted rather than erased. Although Daoud was born and raised in Algeria, he was educated in French and now lives in France since receiving citizenship in 2020. He therefore has the privilege as a man who writes in French under the protection of the French government, and the power to disseminate his writing further than any Algerian before him.

There is a fine line between creativity and exploitation, and Daoud walks dangerously close to it. Whether he crosses it depends on whether he recognises his privilege and honours the survivors, or denies accountability, therefore violating the dignity of those whose pain he channels. This is a small nuance that may render Houris an attack on the people of Algeria, rather than its government.

Daoud defends his decision by pointing to a disturbing generational gap: his own children did not believe that some of the events in his novel had ever occurred. His risk, then, is justified by the need to preserve memory for the next generation, especially in an age when misinformation, extremism, and social media distort history at alarming speeds. This national amnesia is rooted in a generational habit of silence, a coping mechanism embedded in both education and in private family life, making it harder speak, harder to listen, and harder to heal.

He has been accused of instrumentalising civil war trauma for personal gain. But this seems to be just a distraction from the very problem he is trying to address. It is part of a broader pattern in which writers become scapegoats for governments that use silence to avoid accountability. Writers are easier to target than the killers who get away with their massacres and murders, especially when, like Daoud the French part of his identity gives him a complicated relationship with the nation they critique. As an Algerian writing in French, Daoud’s work exists at the tense intersection between France and Algeria. Writers like Daoud and Boualem Sansal act as “hosts of negotiation” between the two countries, therefore their writing, down to the choice of language that they express themselves in, is politicised whether they like it or not. It is a responsibility imposed on them, often tied to guilt and blame, without giving them a choice. Daoud’s Houris, like his previous book, The Mersault Investigation, which gave a direct response to Camus’s The Stranger, embodies the role of literature as the battlefield for unresolved postcolonial guilt, memory, and national identity.

Ultimately the real conflict is not between Daoud and Arbane, or Daoud and the Algerian authorities, but between opposing forces attempting to control the narrative of war, and literature has unwillingly become the site of negotiation. Daoud and Sansal’s critiques of the Algerian state underscore a persistent culture of silencing and repression that has outlived the war. Their work strains diplomatic relations with France yet also exposes the fragility of Algeria’s own national memory.

By suing Daoud, the Algerian state weaponises the survivors’ pain, turning it against the one who dared to give it form. Daoud is accused of weaponising that same pain to indict a state that wants to forget. Both are using trauma as a tool, but for profoundly different ends. Beneath the lawsuits and tense diplomatic relations lies a deeper issue: the necessity of speech in the face of silence. Silence protects oppressors and hides uncomfortable truths, so breaking it inevitably comes at a cost, but in a world where few survivors, especially the women who suffered so much during the war, are able or allowed to speak, Daoud’s decision to do so, however flawed, may not only be justifiable, but necessary.

Leave a comment