For decades, the Assad dynasty ruled Syria with an iron fist, first under Hafez al-Assad and then his son Bashar. The uprising of 2011 was crushed with brutal force, leaving more than 600,000 Syrians dead and millions displaced. On 8 December 2024, after weeks of escalating unrest, the Assad regime was finally overthrown. A transitional council was announced, though questions remain about how this will play out and how stability can be restored. It was a turning point for all Syrians, mixed with fear and uncertainty, but above all, hope. Hope for better times, a Syria for all Syrians.

The fall of the regime after 53 years of oppression and brutality shocked the world. For me, it felt like the closing of a lifetime. I remembered being seven years old in London, when my dad took me to anti-Bashar protests in 2011. Back then, we thought the end was near. I also realised, even at that young age, that visiting my family in Syria would no longer be possible.

Fast forward 13 years: 2024 became an especially significant year for me. For Syrians abroad, the end of the regime felt surreal. Friends messaged me from all corners of the world, describing disbelief and celebration. A group of Oxford students travelled to London to join Syrians celebrating in Trafalgar Square, the same place I had once fought for freedom. For me, the moment was anchored in something more intimate: that summer, before the regime collapsed, I had spent four months volunteering at a migrant centre in Cyprus with Caritas. Though my time there was short, I formed close bonds with Syrian families who gradually opened up about their journeys.

So, when the news broke, my mind went straight to them, families who had risked everything to leave Syria, crossing dangerous seas, only to find themselves living in despicable conditions in Cyprus. I wondered what they felt when they heard the news.

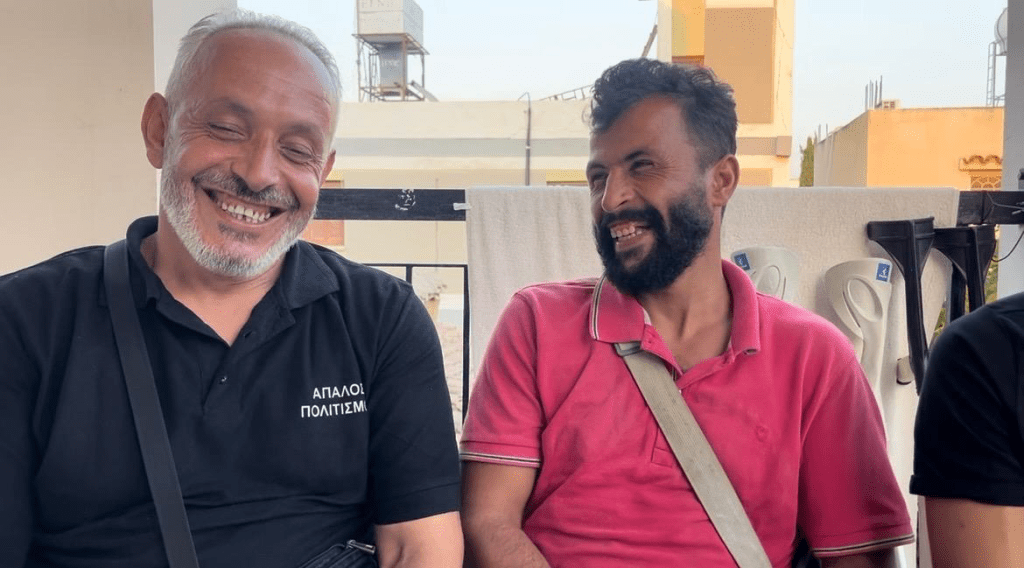

Two men stood out in particular: Abdulrazzak (AR) from Idlib and Youssef from Deir Ez-Zor. They had met in Cyprus’s main detention centre, Pournara, where overcrowding, mouldy food, and lack of support pushed many to despair. Their story touched me deeply, and I interviewed them during my final weeks there.

Youssef had lost his leg on the sea crossing from Lebanon. After seven days at sea, his small boat collided with a rescue vessel, leaving him severely injured. His trauma only deepened when he was taken to Pournara. “I thought about ending my life,” he admitted.

Then he met AR. Years earlier, while working on a construction site in Lebanon to support his family, AR had also lost his leg in an accident. The two bonded immediately, and in the camp became inseparable.

“How did you and Youssef become friends?”

AR: He saw someone other than him with the same disability living normally. So I tried to make things easier for him. Every day, I would ask how he was, encourage him to walk, remind him that he could adapt. God willing, I said, he would find a way forward. We ate, drank, and slept under the same roof. We were only together in the camp for 15 days, but we were with each other 24/7. Even after I left, we spoke on the phone every day.

Eventually, Youssef and AR moved into the same social housing. Their situation is far from unique. With a population of just 1.2 million, Cyprus receives the highest number of asylum applications per capita in Europe. According to UNHCR, in 2024 the island hosted more than 20,000 Syrian asylum seekers, with Pournara camp often holding over twice its intended capacity. Yet conditions remained dire: Asylum seekers in Cyprus are given just €214 a month to live on, while the minimum rent for a 1 bedroom apartment is around €400.

Cyprus: Covid-19 and Detention – Global Detention Project | Mapping immigration detention around the world

When I ask my mother about her happiest memories, she always says: “the days in Qamishli,” a town on the Syria–Turkey border. At the migrant centre, I found myself asking others the same question. As someone who grew up in London, I have always had to live Syria through others’ memories. Too often, the images we see are rubble and ruins. But when Syrians describe home, a different world emerges.

“What are your favourite memories of Syria?”

AR: The land. The trees, the fruit, the agriculture. My family, our gatherings, happiness. All of it was before the war. Now there’s nothing left.

Youssef: Everything was natural in Syria. Before the war, everything was good. Now, nothing is the same. Before, I could walk everywhere. Now I can’t walk more than a short distance. It’s finished.

Others I spoke to shared equally vivid recollections. One woman from Aleppo told me she missed the smell of jasmine in spring. A man from Homs recalled Friday afternoons when his entire extended family would gather for tea. These fragments remind us that Syria is not only defined by its ruins, but also by the everyday rhythms of life people are desperate to recover.

Orange and pomegranate seller, Damascus, 2007, taken from instagram account @syriabefore2011

These are the memories Syrians hold on to, and with the regime gone, they don’t feel quite so impossible to return to.

What are you most excited for in the future?

Youssef: To live as a normal human. That’s all.

We hope to secure our rights, our future, our children’s future. To live like anyone else. I don’t want an unfair life for me or for my children.

Listening to them, I was struck by how basic their dreams were. Not wealth, not power, not even return, just dignity. In human rights language, they were asking for what is fundamental: security, equality, the chance to live without fear. Yet dignity is also the most precarious thing for refugees in Europe today, as shifting policies and rising hostility place their futures in constant uncertainty.

When I reconnected with AR months later, I learned he had resettled in France, hoping his family could soon join him. But tightening EU policies make his future uncertain. Youssef, meanwhile, remains in Cyprus waiting for relocation. Over the past few months, I’ve noticed different initiatives: Syrians I met in Cyprus and elsewhere are posting Instagram stories from Damascus or Aleppo, tentatively returning to see what life might look like after the fall. Yet returning is never simple; it means dropping their asylum claims in Europe and giving up the possibility of resettlement. For many, the decision is agonising: whether to rebuild in Europe, where the bureaucracy is exhausting, or to risk going back to a Syria that is still fragile and unpredictable.

AbdulRazzak and I, Paris, April 2025

The EU has tightened migration rules further in recent years. France now requires 18 months of legal residence before family reunification and proof of French language skills. Austria has suspended family reunification applications for six months due to “overburdened services.” Germany has gone further, suspending reunification for two years for those under subsidiary protection. For people like Abdulrazzak and Youssef, these rules mean their hopes of rebuilding family life remain fragile.

When my mother spoke of her childhood in Qamishli, she painted a Syria that seemed distant and unreachable. But on 8 December, that memory no longer felt like a relic. It felt like a possibility. The regime’s fall cannot erase the suffering, nor can it guarantee peace. But it revives the most radical hope of all: that Syrians might one day live ordinary lives again.

So, when I watched the Assad regime fall, I thought of them. Will Syrians ever be able to return to the Syria they remembered? Would they be able to live the dignified, ordinary lives they dreamed of? It is easy to get caught up in political headlines, power struggles, and factions. But we must not forget the real faces of the revolution: civilians who endured unthinkable hardship yet still carry one simple, universal hope, to live as normal humans.

Aleppo Nights, 2009, by Zachary Rosenfeld, @syriabefore2011

Leave a comment