Prior to the turn of the century among both near-Eastern and Western scholars, the status quo narrative of Mongol conquest, expansion, and rule of Eurasia from the 13th to 15th centuries gives the Mongols an overwhelmingly singular reputation: brutish, merciless, and unintelligent. In the past few decades, however, the tide of this characterisation in scholarship has begun to turn. More detail and credit are being afforded to Mongolian history and political intelligence, literature exists to explore why their role in history is as two-dimensional as it has been for so long, and prominent authors are consistently acknowledging the connectivity and cultural reinvigoration that underscored Mongol rule over the Middle East. In all, this shift has led to a rather equal division in literature and a turning point in how history understands the Mongols. For the sake of both ethical considerations and historical accuracy, it is equally necessary to reconcile the havoc that the Mongols wreaked and to deviate from the decidedly superficial role of “the barbarians” that they have been afforded for the better part of documented medieval history. In the interest of this balance, this essay will posit that while it is fair to call the Mongols’ invasion and rule over the Middle East destructive, as per their common reputation, there are also logical and ethical flaws in the notion that the Mongols were purely violent and chaotic as a sociopolitical force. Credit must also be afforded to the Mongols’ conscious facilitation of a cultural synthesis in the Islamic world through trade and assimilation to the existing social and political structures of annexed communities, albeit with great caution of the modern politics underscoring this rhetoric.

While lacking nuance, the dominant status quo understanding of the Mongols as a destructive enterprise does have significant merit. While primary sources themselves are not unanimous regarding the extent of the damage, with many scholars not even attempting to estimate a total death toll, consensus exists that the killings from Mongol invasion of the Middle East were disproportionately high and an abysmal tragedy. Jackson (2017) describes the conquest as “indiscriminate killing,” “put[ting] men, women, and children to the sword,” and “merely kill[ing] or wound people” rather than engaging in looting, arson, or the killing of livestock as were the standards for destruction in warfare of the time (Jackson, 2017, p. 157). Much of this death toll can also likely be attributed to the Mongols’ signature “tsunami strategy,” a term coined by Timothy May to describe a specific system of Mongol attack that annexed territory by inducing indiscriminate maximum damage. Via this strategy, the Mongols devastated an area and then retreated, leaving a “broad belt” of destruction (May, 2024). They subsequently occupied and officially annexed only part of this area, leaving the rest weak and vulnerable enough so that they were unable to resist annexation later, but not so ruined that the land could not be cultivated later within their empire. Chaos-sowing tactics also extended beyond the battlefield, with the Mongols being known to forge letters from native political and military figures to engineer distrust within an enemy population (Jackson, 2017, p. 87). The devastation was also not limited to the Mongol era of conquest. “Rapacious and irregular taxation,” especially in the earlier years of Mongol rule of the Middle East, brought about widespread financial ruin in addition to the human cost of constructing the largest contiguous empire in history (Jackson, 2017).

However, it must be acknowledged that this destruction as a basis for characterising the entirety of Mongol rule is both unintuitive and derived in part from stereotypes about non-sedentary civilizations. A wave of this understanding became popular among Western scholars at the turn of the century, with the first major articulation coming in 2006 from Bert Fragner (Jackson, 2017). He argues that modern authors have a tendency to understand the Mongols as uncivilized aggressors in part because of a perceived dichotomy between the “respectably old and well-established cultural units” of the sedentary cultures they conquered versus the “novel, history-less” one of the Mongols (Fragner, 2006, p. 68). Within this framework, the loss of a long-established civilization as the Abbasid Dynasty to a wholly destructive, ephemeral enterprise is an injustice and a tragedy. /To this, he emphasizes that a more holistic understanding of what it means to be a non-sedentary culture from the steppe continent is necessary:

“We perceive of them– the sedentaries– as the main transmitters and bearers of history and tradition, whilst we are clearly inclined to see the Mongol invaders as rather bare and stripped of any kind of history… From the Mongol conquerors’ vantage point, it was rather the Mongols themselves who possessed history.” (Fragner, 2006, p. 69)

Fragner continues to argue that with this reframed understanding of the Mongols as a historic peoples with an independent history and a complex understanding of the world, it becomes possible to understand the Mongols as not an entirely destructive enterprise of barbarians and pillagers whose existence begins and ends with the effect they had on sedentary civilization. Rather, they become a community with the historical capacity for building as much as conquering. Once the Mongols are afforded the same ideological and effective complexity as their settled neighbors, possibilities for acknowledging the existing benefits of their rule and amend the “entirely destructive” Mongol reputation are expanded.

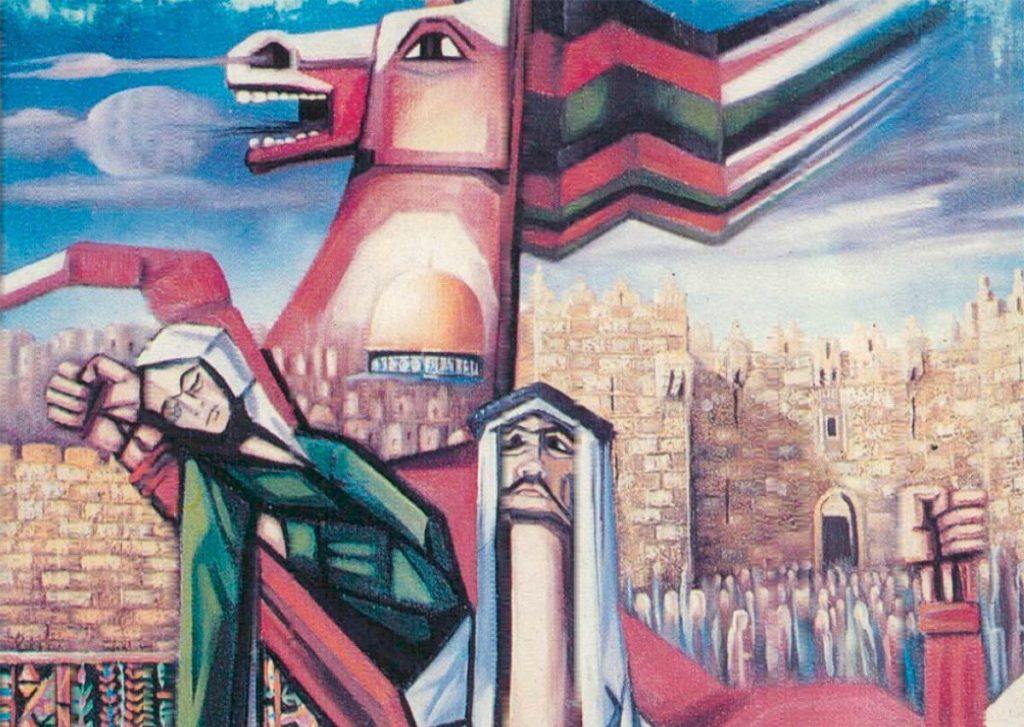

One of these existing benefits is the intentional manner in which the Mongols brought about a cultural synthesis in the Islamic world, especially in their thriving system of trade connectivity. Firstly, by nature of the sheer size of the empire uniting the majority of Eurasia, the Silk Road served as an powerful means for cultural transmission. On the basis of the Silk Road cultural exchange, S.A.M. Adshead describes Mongol expansion as a whole as “the first global event.” Within this event, the Silk Road was “the basic information circuit” with sustained East-West accessibility at its center (Adshead, 1993). In fields ranging from medicine, to cuisine, to geography, an intellectual exchange is evidenced in a rapid period of innovation that scholars have also labeled “the Chinggis Exchange” or “the Persian Renaissance” (May, 2012; Lane, 2003). The trade-based cultural synthesis of the Islamic world in the era is perhaps best exemplified by the flourishing of cross-cultural art forms. One particularly valuable example is gold brocade, which was fashioned from Tibetan gold, weaving techniques from Baghdad, and silk from China (Allsen, 2002). It is also clear that this cultural revolution was not simply a passive byproduct of the Mongol Empire’s size. The cultural flourishing of the Silk Road is, far more often than not, classified as deliberate in recent literature, evidenced by Mongol construction of novel infrastructure along the silk road such as relay posts and sophisticated horse messenger systems (Jackson, 2017, p. 5).

The deliberate cultural confluence induced by Mongol rule is also exemplified in their ruling systems; the Mongols intentionally assimilated themselves to the existing aristocratic, class, and rhetorical infrastructure of the Islamic world they conquered. This is first demonstrated in the pre-fragmented Mongol empire of Chinggis Khan and Hulegu, as the empire allowed for individual regions to retain their religious identities and continue being governed by Mongol-approved local administrators (Jackson, 2017). The Mongols also adopted Islamic titles, rituals, and imagery deeply reminiscent of those used by the Abbasids and caliphs from earlier Islamic dynasties, thus establishing political legitimacy within the framework of the Abbasid rule that preceded them. However, Mongol assimilation as a means to promote unity and legitimacy is demonstrated clearest in the Ilkhanate, or Mongol-ruled Persia, which followed the empire’s fragmentation in 1261 (Jackson, 2017, p. 151). Firstly, rather than dismantling the Islamic and Abbasid bureaucratic and aristocratic traditions, Mongol leaders in the Ilkhanate co-opted them, often allowing local elites to retain their authority (Morgan, 2007). The Ilkhanate additionally continued Abbasid patronage of academia through constructing libraries and madrasas, retained Persian as the language of administration, and continued to appoint native Iranians as viziers. Lastly, by converting to Islam in the late 13th century under Ghazan Khan, the Mongol elite seem to completely embed themselves into the religious and ideological frameworks that underpinned political legitimacy in the Islamic world they conquered (Jackson, 2017). If Mongol rule was not already a unifying force, this functionally complete religious and cultural assimilation allowed their authority to serve as a unifying vessel through which the development of Islamic thought and society could continue. This idea is articulated well in the context of Mongol rule as a whole by Berkey (2003):

“Far from marking an end, the Mongol invasions provided an opportunity for solidifying and extending the social, political, and religious developments of the previous two centuries.” (Berkey, 2003, p. 184)

In line with the theme of rhetoric that underscores this discussion, however, it is essential to note that these new-age positive narratives of the Mongols are largely western-driven and seem just as politically informed as the dominant narrative. This is firstly because the beginning of the wave of scholarship that highlights the benefits of Mongol invasion and rule of the Islamic world roughly coincides with the turn of the century and the onset of the War on Terror (Jackson, 2017). At the same time, antagonists of the War on Terror were known to thematically refer to the Mongols as a brutish and devastating enterprise akin to the modern Western world. Osama bin Laden, for example, stated in an Al-Jazeera statement broadcast in 2002 that “Cheney and Powell killed and destroyed in Baghdad [during the First Gulf War] more than Hulegu [sic] of the Mongols” (Jackson, 2017, p. 3). It thus seems entirely possible that the growth of the Islamic world as an enemy in the period is linked to the concurrently growing positive view of the Mongols, who had historically been a prominent enemy of the Islamic world. As it follows, this benefit-based shift in literature was almost entirely exclusive to western born and educated scholars. Bernard Lewis, Bert Fragner, and Thomas T. Allsen, for example, are a few scholars who seem to be at the helm of the emphatically positive narrative of the Mongols sweeping the academic world. Homa Katouzian, on the other hand, is a Persian scholar whose narrative is markedly distinct, despite publishing in the same timeframe. As articulated by Katouzian, any attempt to find an upside, or even “a balance for these disasters, would be reminiscent…of the pious belief that the earthquake of Lisbon had some beneficial effects such as dogs being able to help themselves to the corpses of the dead” (Katouzian, 2006, p. 4). Given the timing of the positive-leaning shift in the Mongol legacy against global events and the geography of its popularity, it is not difficult to indict this shift in literature for its political undertones. Thus, while nuance is necessary to the telling of any history, caution and rhetorical awareness are equally necessary. The positive-leaning historical lens is underscored by its own modern political biases, and complete subscription to the narrative risks of overcorrecting and undermining a factual early history of extreme violence.

In all, it would be both historically inaccurate and an ethical disservice to fail to acknowledge the destruction wreaked by Mongol invasion, rule, and toppling of the Abbasid dynasty’s authority of the Islamic world. As literature distances itself farther from the notion of this destruction being the sole reputation of the Mongols, this fact does require elaboration lest the field overcorrects into arguments about the Mongols as a historical “net positive.” However, it would equally be a disservice to characterize the Mongols’ rule as “entirely destructive” given the bias and logical failures surrounding the reputation, and given the aspects of their rule that did intentionally allow for native cultural progress and unity. Through conscious construction of trade infrastructure and codified assimilation to preexisting norms within the newly subjugated Middle East, the Mongols did facilitate a cultural synthesis in the Islamic world. While there remains an ethical danger of overcorrecting and undermining the violence of the 13th century Mongol invasion, Mongol rule over the Islamic world is definitively not the two-dimensional story of barbarism it is often understood to be, and its legacy must be painted with all the criticisms, credit, and rhetorical awareness that it is due.

by Hana Mahyoub

References

Adshead, S. A. M. (1993). Central asia in world history. Palgrave Macmillan.

Allsen, T. T. (2002). Commodity and exchange in the Mongol Empire: A cultural history of Islamic textiles. Cambridge University Press.

Berkey, J. P. (2003). The formation of Islam: Religion and society in the Near East, 600-1800. Cambridge University Press.

Deweese, D. (2009). Islamization in the mongol empire. In N. Di Cosmo, A. J. Frank, & P. B. Golden (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Inner Asia (1st ed., pp. 120–134). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139056045.010

Fragner, B. G. (2006). Ilkhanid rule and its contributions to iranian political culture. In L. Komaroff (Ed.), Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan (pp. 68–80). BRILL. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789047418573_007

Jackson, P. (2017). The Mongols and the Islamic world: From conquest to conversion. Yale University Press.

Katouzian, H. (2010). The Persians: Ancient, medieval and modern Iran (First printed in paperback). Yale Univ. Press.

Lane, G. E. (2003). Early mongol rule in thirteenth-century iran (0 ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203417874

May, T. (2024). Routledge handbook of medieval military strategy (J. D. Hosler & D. P. Franke, Eds.). Routledge.

May, T. M. (2012). The Mongol conquest in world history. Reaktion Books.

Morgan, D. O. (2007). The mongols (2nd ed). Blackwell Publishing.

Leave a comment